Fabian Dablander Postdoc Behavioural Data Science & Sustainability

Two properties of the Gaussian distribution

In a previous blog post, we looked at the history of least squares, how Gauss justified it using the Gaussian distribution, and how Laplace justified the Gaussian distribution using the central limit theorem. The Gaussian distribution has a number of special properties which distinguish it from other distributions and which make it easy to work with mathematically. In this blog post, I will focus on two of these properties: being closed under (a) marginalization and (b) conditioning. This means that, if one starts with a $p$-dimensional Gaussian distribution and marginalizes out or conditions on one or more of its components, the resulting distribution will still be Gaussian.

This blog post has two parts. First, I will introduce the joint, marginal, and conditional Gaussian distributions for the case of two random variables; an interactive Shiny app illustrates the differences between them. Second, I will show mathematically that the marginal and conditional distribution do indeed have the form I presented in the first part. I will extend this to the $p$-dimensional case, demonstrating that the Gaussian distribution is closed under marginalization and conditioning. This second part is a little heavier on the mathematics, so if you just want to get an intuition you may focus on the first part and simply skip the second part. Let’s get started!

The Land of the Gaussians

In the linear regression case discussed previously, we have modeled each individual data point $y_i$ as coming from a univariate conditional Gaussian distribution with mean $\mu = x_i^Tb$ and variance $\sigma^2$. In this blog post, we introduce the random variables $X_1$ and $X_2$ and assume that both are jointly normally distributed; we are going from $p = 1$ to $p = 2$ dimensions. The probability density function changes accordingly — it becomes a function mapping from two to one dimension, i.e., $f: \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+$.

To simplify notation, let $\mathbf{x} = (x_1, x_2)^T$ and $\mathbf{\mu} = (\mu_1, \mu_2)^T$ be two 2-dimensional vectors denoting one observation and the population means, respectively. For simplicity, we set the population means to zero, i.e. $\mathbf{\mu} = (0, 0)$. In one dimension, we had just one parameter for the variance $\sigma^2$; in two dimensions, this becomes a symmetric $2 \times 2$ covariance matrix

\[\Sigma = \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_1^2 & \rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \\ \rho \sigma_1\sigma_2 & \sigma_2^2 \end{pmatrix} \enspace ,\]where $\sigma_1^2$ and $\sigma_2^2$ are the population variances of the random variables $X_1$ and $X_2$, respectively, and $\rho$ is the population correlation between the two. The general form of the density function of a $p$-dimensional Gaussian distribution is

\[f(\mathbf{x} \mid \mathbf{\mu}, \Sigma) = (2\pi)^{-p/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2} (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{\mu})^T \Sigma^{-1}(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{\mu}) \right) \enspace ,\]where $\mathbf{x}$ and $\mathbf{\mu}$ are a $p$-dimensional vectors, $\Sigma^{-1}$ is the $(p \times p)$-dimensional inverse covariance matrix and $|\Sigma|$ is its determinant.1 We focus on the simpler 2-dimensional, zero-mean case. Observe that

\[\Sigma^{-1} = \frac{1}{|\Sigma|} \begin{pmatrix}\sigma^2_2 & -\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \\ -\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 & \sigma^2_1\end{pmatrix} = \frac{1}{\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \begin{pmatrix}\sigma^2_2 & -\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \\ -\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 & \sigma^2_1\end{pmatrix} \enspace ,\]which we use to expand the bivariate Gaussian density function:

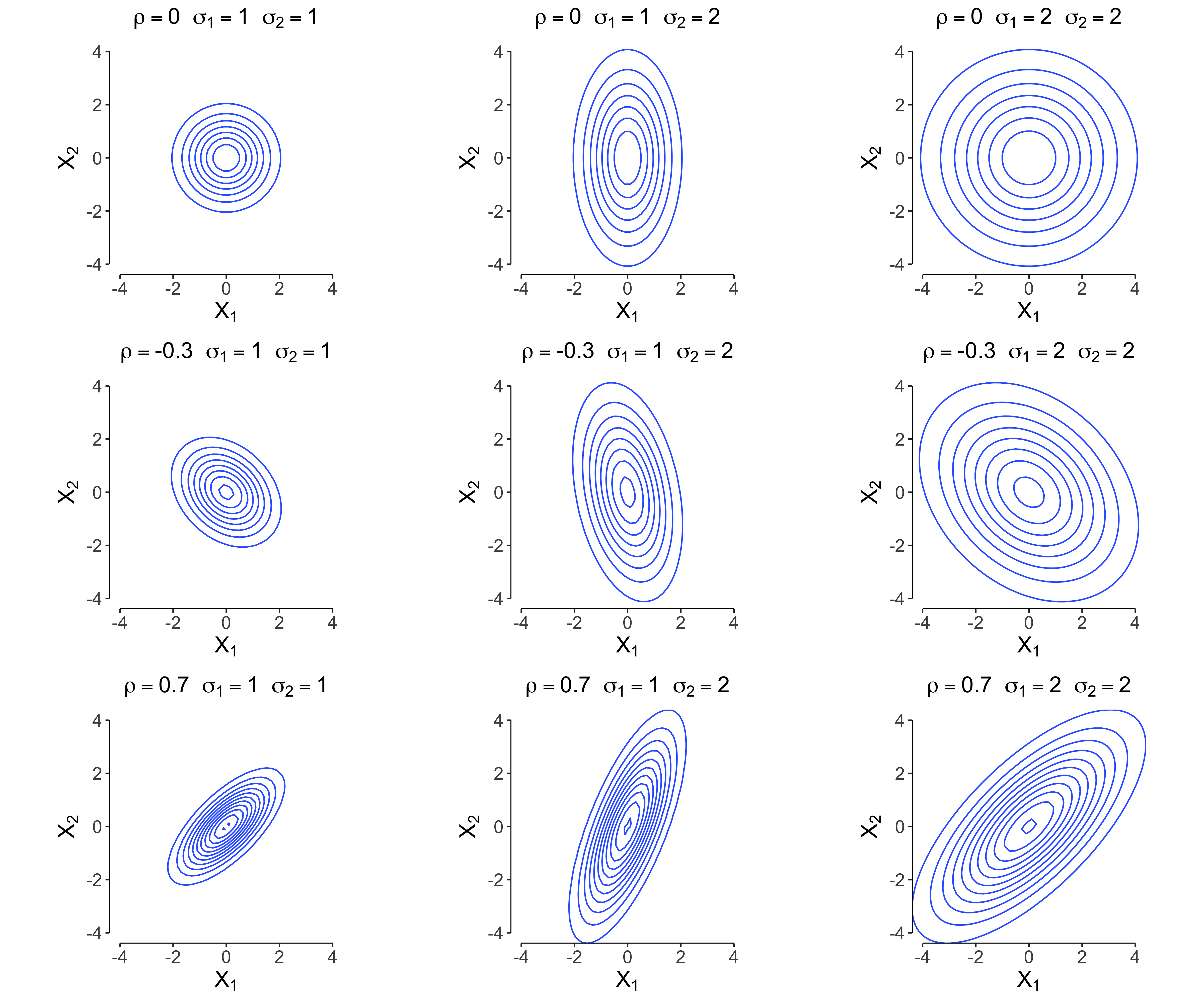

\[\begin{aligned} f(x, y \mid \sigma_1^2, \sigma_2^2, \rho) &= \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \end{pmatrix}^T \begin{pmatrix}\sigma^2_2 & -\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \\ -\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 & \sigma^2_1\end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \end{pmatrix} \right) \\[1em] &= \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \begin{pmatrix} x_1 \sigma^2_2 -x_2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \\ x_2 \sigma^2_1 -x_1\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \end{pmatrix}^T \begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \end{pmatrix} \right) \\[1em] &= \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma_1^2 x_2^2\bigg] \right) \enspace . \end{aligned}\]The figure below plots the contour lines of nine different bivariate normal distributions with mean zero, correlations $\rho \in [0, -0.3, 0.7]$, and standard deviations $\sigma_1, \sigma_2 \in [1, 2]$.

In the top row, all bivariate Gaussian distributions have $\rho = 0$ and look like a circle for standard deviations of equal size. The top middle plot is stretched along $X_2$, giving it an elliptical shape. The middle and last row show how the distribution changes for negative ($\rho = -0.3$) and positive ($\rho = 0.7$) correlations.2

In the remainder of this blog post, we will take a closer look at two operations: marginalization and conditioning. Marginalizing means ignoring, and conditioning means incorporating information. In the zero-mean bivariate case, marginalizing out $X_2$ results in

\[f(x_1) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_1^2}} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma_1^2} x_1^2\right) \enspace ,\]which is a simple univariate Gaussian distribution with mean $0$ and variance $\sigma_1^2$. On the other hand, incorporating the information that $X_2 = x_2$ results in

\[f(x_1 \mid x_2) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_1^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma_1^2(1 - \rho^2)} \left(x_1 - \rho \frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_2} x_2\right)^2\right) \enspace ,\]which has mean $\rho \frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_2} x_2$ and variance $\sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)$. The next section provides two simple examples illustrating the difference between these two types of distributions, as well as a simple Shiny app that allows you to build an intuition for conditioning in the bivariate case.

Two examples and a Shiny app

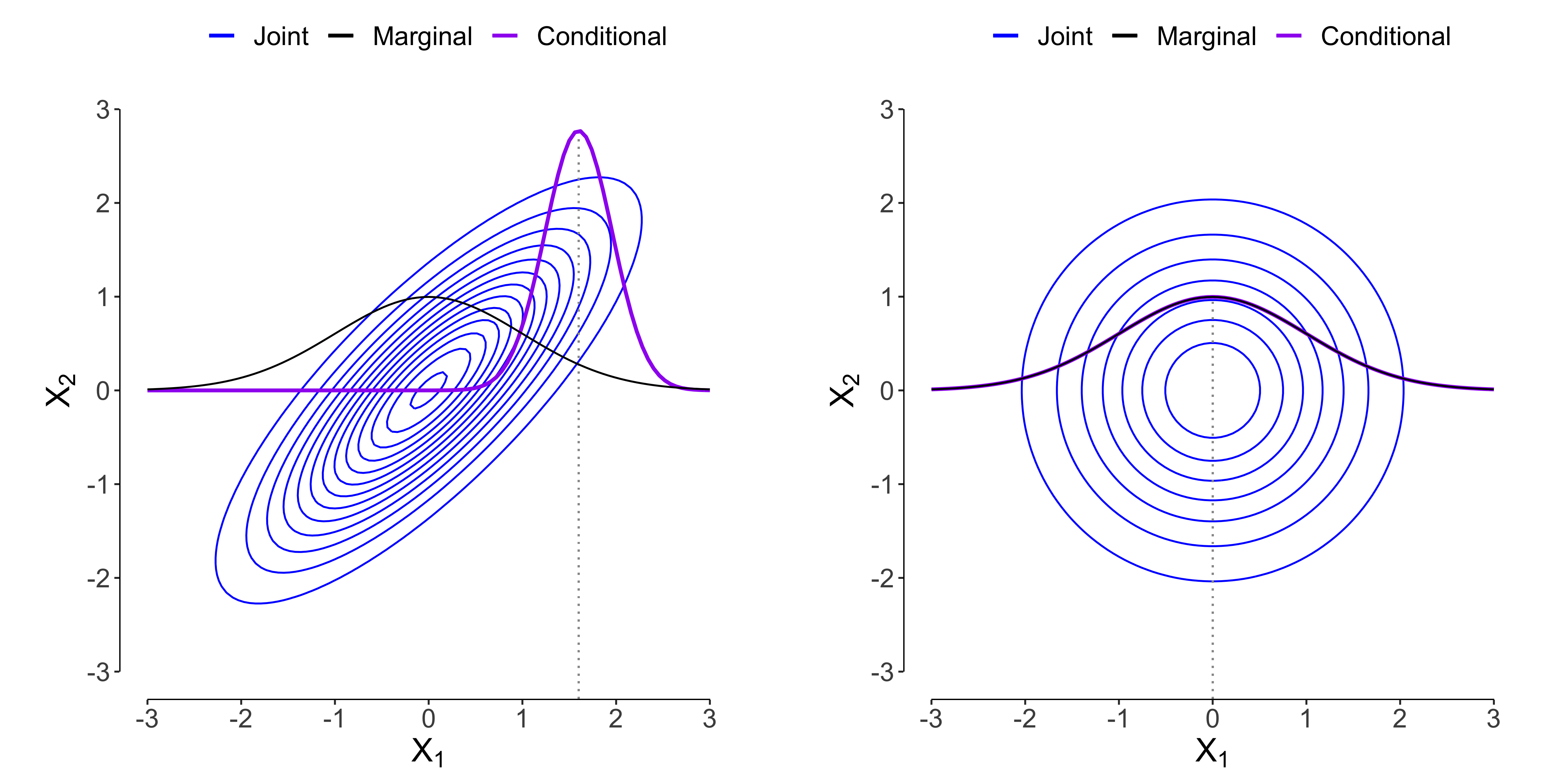

Let’s illustrate the difference between marginalization and conditioning on two simple examples. First, assume that the correlation is very high with $\rho = 0.8$, and that $\sigma_1^2 = \sigma_2^2 = 1$. Then, observing for example $X_2 = 2$, our belief about $X_1$ changes such that its mean gets shifted to the observed $x_2$ value, i.e. $\mu_1 = 0.8 \cdot 2 = 1.6$ (indicated by the dotted line in the Figure below). The variance of $x_1$ gets substantially reduced, from $1$ to $(1 - 0.8^2) = 0.36$. This is what the left part in the Figure below illustrates. If, on the other hand, $\rho = 0$ such that $X_1$ and $X_2$ are not related, then observing $X_2 = 2$ changes neither the mean of $X_1$ (it stays at zero), nor its variance (it stays at 1); see the right part of the Figure below. Note that the marginal and conditional densities are multiplied with a constant to make them better visible.

To explore the relation between joint, marginal, and conditional Gaussian distributions, you can play around with a Shiny app following this link. In the remainder of the blog post, we will prove that the two distributions given above are in fact the marginal and conditional distributions in the two-dimensional case. We will also generalize these results to $p$-dimensional Gaussian distributions.

The two rules of probability

In the second part of this blog post, we need the two fundamental ‘rules’ of probability: the sum and the product rule.3 The sum rule states that

\[p(x) = \int p(x, y) \, \mathrm{d}y \enspace ,\]and the product rule states that

\[p(x, y) = p(x \mid y) \, p(y) = p(y \mid x) \, p(x) \enspace .\]In the remainder, we will see that a joint Gaussian distribution can be factorized into a conditional Gaussian and a marginal Gaussian distribution.

Property I: Closed under Marginalization

The first property states that if we marginalize out variables in a multivariate Gaussian distribution, the result is still a Gaussian distribution. The Gaussian distribution is thus closed under marginalization. Below, I will show this for a bivariate Gaussian distribution directly, and for an arbitrary dimensional Gaussian distributions by thinking rather than computing. This illustrates that knowing your definitions can help avoid tedious calculations.

2-dimensional case

To show that the marginalisation property holds for the bivariate Gaussian distribution, we need to solve the following integration problem

\[\int_{X_2} f(x_1, x_2 \mid \sigma_1^2, \sigma_2^2, \rho) \, \mathrm{d} x_2 \enspace ,\]and check whether the result is a univariate Gaussian distribution. We tackle the problem head on and expand

\[\begin{aligned} &\int_{X_2} \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma_1^2 x_2^2\bigg] \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \\[0.5em] &= \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \sigma_2^2 x_1^2\right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[\sigma_1^2 x_2^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2\bigg] \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \\[1em] &= \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \sigma_2^2 x_1^2\right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[x_2^2 - 2\rho \frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1 x_2\bigg] \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \enspace . \end{aligned}\]Putting everything that does not involve $x_2$ outside the integral, we’ve come quite far! Note that we can “complete the square”, that is, write

\[x_2^2 - 2\rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1 x_2 = \left(x_2 - \rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1\right)^2 - \rho^2\frac{\sigma_2^2}{\sigma_1^2} x_1^2 \enspace .\]This leads to

\[\begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \sigma_2^2 x_1^2\right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[\left(x_2 - \rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1\right)^2 - \rho^2\frac{\sigma_2^2}{\sigma_1^2} x_1^2\bigg] \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \\[1em] =&\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 + \frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \rho^2\frac{\sigma_2^2}{\sigma_1^2} x_1^2 \right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \left(x_2 - \rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1\right)^2 \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \\[1em] =&\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1(1 - \rho^2)} x_1^2 + \frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1(1 - \rho^2)} \rho^2 x_1^2 \right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \left(x_2 - \rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1\right)^2 \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \\[1em] =&\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{x_1^2 - \rho^2 x_1^2}{2\sigma^2_1(1 - \rho^2)} \right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \left(x_2 - \rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1\right)^2 \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \\[1em] =&\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{x_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}{2\sigma^2_1(1 - \rho^2)} \right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \left(x_2 - \rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1\right)^2 \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \\[1em] =&\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1} x_1^2\right) \int_{X_2} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \left(x_2 - \rho\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1\right)^2 \right) \mathrm{d} x_2 \enspace . \end{aligned}\]We are nearly done! What’s left is to realize that the integrand is the kernel of a univariate Gaussian distribution with mean $\rho \frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1} x_1$ and variance $\sigma_2^2 (1 - \rho^2)$ — it’s an unnormalized conditional Gaussian distribution! The thing that makes a Gaussian distribution integrate to 1, as all distributions must, is the normalizing constant in front, the strange term involving $\pi$. For this particular distribution, the normalizing constant is $\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_2^2 (1 - \rho^2)}$.4

Continuing, we arrive at the solution

\[\begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1} x_1^2\right) \sqrt{2\pi \sigma_2^2 (1 - \rho^2)} \\[0.5em] &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_1^2}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1} x_1^2\right) \enspace , \end{aligned}\]which is the density function of the univariate Gaussian distribution (with mean zero). With some work, we have shown that marginalizing out a variable in a bivariate Gaussian distribution leads to a univariate Gaussian distribution. This process ‘removes’ any occurances of the correlation $\rho$ and the other variable $x_2$.

Granted, this process was rather tedious and not at all general (but good practice!) — does it also work when going from 3 to 2 dimensions? Will the remaining bivariate distribution be Gaussian? What if we go from 200 dimensions to 97 dimensions?

$p$-dimensional case

A more elegant way to see that a $p$-dimensional Gaussian distribution is closed under marginalization is the following. First, we note the requirement that a random variable needs to fulfill in order to have a (multivariate) Gaussian distribution.

Definition. $\mathbf{X} = (X_1, \ldots, X_p)^T$ has a multivariate Gaussian distribution if every linear combination of its components has a (multivariate) Gaussian distribution. Formally,

\[\mathbf{X} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, \Sigma) \,\,\,\, \text{if and only if} \,\,\,\, A\mathbf{X} \sim \mathcal{N}(A\mu, A\Sigma A^T) \enspace ,\]see for example Blitzstein & Hwang (2014, pp. 309-310).

Second, from this it immediately follows that any subset of random variables $H \subset X$ are themselves normally distributed, and the mean and covariance is given by simply ignoring all elements that are not in $H$; this is called the marginalisation property. In particular, we choose a linear transformation that simply ignores the components we want to marginalize out. As an example, let’s take the trivariate Gaussian distribution

\[\begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N}\left( \begin{pmatrix} \mu_1 \\ \mu_2 \\ \mu_3 \\ \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_1^2 & & \\ \rho_{12}\sigma_1\sigma_2 & \sigma_2^2 & \\ \rho_{13}\sigma_1\sigma_3 & \rho_{23}\sigma_2\sigma_3 & \sigma_3^2 \\ \end{pmatrix} \right) \enspace ,\]which has a three-dimensional mean vector and adds a variance and two correlations to the (symmetric) covariance matrix. Define

\[A = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0\end{pmatrix} \enspace ,\]which picks out the components $X_1$ and $X_2$ and ignores $X_3$. Putting this into the equality from the definition, we arrive at

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0\end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \end{pmatrix} &\sim \mathcal{N}\left( \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0\end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \mu_1 \\ \mu_2 \\ \mu_3 \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0\end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_1^2 & & \\ \rho_{12}\sigma_1\sigma_2 & \sigma_2^2 & \\ \rho_{13}\sigma_1\sigma_3 & \rho_{23}\sigma_2\sigma_3 & \sigma_3^2 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0\end{pmatrix} \right) \\[1em] \begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \end{pmatrix} &\sim \mathcal{N}\left( \begin{pmatrix} \mu_1 \\ \mu_2 \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_1^2 & \\ \rho_{12}\sigma_1\sigma_2 & \sigma_2^2 \end{pmatrix} \right) \enspace . \end{aligned}\]Two points to wrap up. First, it helps to know your definitions. Second, in the Gaussian case, computing marginal distributions is trivial. Conditional distributions are a bit harder, unfortunately. But not by much.

Property II: Closed under Conditioning

Conditioning means incorporating information. The fact that Gaussian distributions are closed under conditioning means that, if we start with a Gaussian distribution and update our knowledge given the observed value of one of its components, then the resulting distribution is still Gaussian — we never have to leave the wonderful land of the Gaussians! In the following, we prove this first for the simple bivariate case, which should also give some intuition as to how conditioning differs from marginalizing, and then provide the more general expression for $p$ dimensions.

Instead of ignoring information, as we did when computing marginal distributions above, we now want to incorporate information we have about the other random variable $X_2$. Conditioning implies learning: how does our knowledge that $X_2 = x_2$ change our knowledge about $X_1$?

2-dimensional case

Let’s say we observe $X_2 = x_2$. How does that change our beliefs about $X_1$? The product rule above leads to Bayes’ rule (via simple division), which is exactly what we need:

\[f(x_1 \mid x_2) = \frac{f(x_1, x_2)}{f(x_2)} \enspace ,\]where we have suppressed conditioning on the parameters $\rho, \sigma_1^2, \sigma_2^2$ to avoid cluttered notation. Let’s do some algebra! We write

\[\begin{aligned} f(x_1 \mid x_2) &= \frac{\frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 \sigma_2^2(1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma_1^2 x_2^2\bigg] \right)}{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_2^2}} \exp \left( -\frac{1}{2\sigma_2^2} x_2^2\right)} \\[1em] &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma_1^2 x_2^2\bigg] + \frac{1}{2\sigma_2^2} x_2^2 \right) \enspace , \end{aligned}\]which already looks promising. Putting the $x_2^2$ term into the angular brackets, we should see a nice quadratic formula:

\[\begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma_1^2 x_2^2 - \frac{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)}{2\sigma_2^2} x_2^2 \bigg] \right) \\[1em] &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma_1^2 x_2^2 - \sigma^2_1 (1 - \rho^2) x_2^2 \bigg] \right) \\[1em] &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma_1^2 x_2^2 - \sigma_1^2 x_2^2 + \sigma_1^2 \rho^2 x_2^2 \bigg] \right) \\[1em] &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 \sigma^2_2(1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[ \sigma_2^2 x_1^2 - 2\rho \sigma_1 \sigma_2 x_1 x_2 + \sigma^2_1 \rho^2 x_2^2 \bigg] \right) \\[1em] &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 (1 - \rho^2)} \bigg[x_1^2 - 2\rho \frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_2} x_1 x_2 + \frac{\sigma^2_1}{\sigma^2_2 } \rho^2 x_2^2 \bigg] \right) \\[1em] &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_1^2 (1 - \rho^2)}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2_1 (1 - \rho^2)} \left(x_1 - \rho \frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_2} x_2 \right)^2 \right) \enspace . \end{aligned}\]Done! The conditional distribution has a mean of $\rho \frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_2}x_2$ and a variance of $\sigma_1^2(1 - \rho^2)$. How does this look like in $p$ dimensions?

$p$-dimensional case

We need a little bit more notation for the crazy ride we’re about to embark on. Let $\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \ldots, x_n)^T$ be an $n$-dimensional vector and $\mathbf{y} = (y_1, \ldots, y_m)^T$ an $m$-dimensional vector which both are jointly Gaussian distributed with covariance matrix $\Sigma \in \mathbb{R}^{(n + m) \times (n + m)}$. Note that we can write $\Sigma$ as a block matrix, i.e.,

\[\Sigma = \begin{pmatrix} \Sigma_{xx} & \Sigma_{xy} \\ \Sigma_{yx} & \Sigma_{yy} \end{pmatrix} \enspace ,\]where $\Sigma_{xx}$ and $\Sigma_{yy}$ are the covariance matrices of $\mathbf{x}$ and $\mathbf{y}$, respectively, and $\Sigma_{xy} = (\Sigma_{yx})^T$ gives the covariance between $\mathbf{x}$ and $\mathbf{y}$. We remember the density function of a multivariate Gaussian distribution from above, and take a first stab:

\[\begin{aligned} f(\mathbf{x} \mid \mathbf{y}) &= \frac{f(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})}{f(\mathbf{y})}\\[.5em] &= \frac{(2\pi)^{-(n + m) / 2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix}^T \Sigma^{-1} \begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix}\right]\right)}{(2\pi)^{-m/2}|\Sigma_{yy}|^{-1/2}\text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\mathbf{y}^T \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right]\right)} \\[1em] &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix}^T \begin{pmatrix} \Sigma_{xx} & \Sigma_{xy} \\ \Sigma_{yx} & \Sigma_{yy} \end{pmatrix}^{-1} \begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix}\right] + \mathbf{y}^T \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right) \\[1em] &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix}^T \begin{pmatrix} \Sigma_{xx} & \Sigma_{xy} \\ \Sigma_{yx} & \Sigma_{yy} \end{pmatrix}^{-1} \begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix} - \mathbf{y}^T \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right]\right) \enspace . \end{aligned}\]There’s only a slight problem. The inverse of the block matrix is pretty ugly:

\[\Sigma^{-1} = \begin{pmatrix} \left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx} \right)^{-1} & -\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \\ -\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1} & \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} + \Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma{yx}\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \end{pmatrix} \enspace ,\]where $\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}$ is the Schur complement of $\Sigma_{xx}$ in the block matrix above. Let’s be lazy and delay computation by simply renaming the relevant parts, i.e.,

\[\Omega = \begin{pmatrix} \Omega_{xx} & \Omega_{xy} \\ \Omega_{yx} & \Omega_{yy} \end{pmatrix} = \Sigma^{-1} \enspace .\]Proceeding bravely, we write

\[\begin{aligned} f(\mathbf{x} \mid \mathbf{y}) &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix}^T \begin{pmatrix} \Omega_{xx} & \Omega_{xy} \\ \Omega_{yx} & \Omega_{yy} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix} - \mathbf{y}^T \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right]\right) \\[1em] &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xx} + \mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{yx} \\ \mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xy} + \mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{yy} \end{pmatrix}^T \begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{y}\end{pmatrix} - \mathbf{y}^T \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right]\right) \\[1em] &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[ \mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xx} \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{yx} \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} + \mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{yy} \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{y}^T \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right]\right) \\[1em] &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[ \mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xx} \mathbf{x} + 2\mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} + \mathbf{y}^T \left(\Omega_{yy} - \Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\right) \mathbf{y}\right]\right) \enspace , \end{aligned}\]where we get the last line by noting that $\mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{yx} \mathbf{x} = \left(\mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y}\right)^T$, i.e. they give the same scalar. It is also important to keep in mind that $ \Omega_{yy} \neq \Sigma_{yy}^{-1}$.

There is hope: we are in an analogous situation as in the two-dimensional case described above. Somehow we must be able to ‘‘complete the square’’ in the more general $p$-dimensional case, too.

Scribbling on paper for a bit, we dare to conjecture that the conditional distribution is

\[f(\mathbf{x} \mid \mathbf{y}) = (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(\mathbf{x} + \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y}\right)^T\Omega_{xx}\left(\mathbf{x} + \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} \right)\right) \enspace ,\]which expands into

\[\begin{aligned} &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\mathbf{x}^T\Omega_{xx}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xx} \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} + \mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{xy}^{T} \Omega_{xx}^{-T} \Omega_{xx}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{xy}^T \Omega_{xx}^{-T} \Omega_{xx} \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} \right]\right) \\[1em] &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left[\mathbf{x}^T\Omega_{xx}\mathbf{x} + 2\mathbf{x}^T \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} + \mathbf{y}^T \Omega_{yx} \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} \right]\right) \enspace . \end{aligned}\]For our conjecture to be true, it must hold that

\[\Omega_{yy} - \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} = \Omega_{yx} \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \enspace .\]Indeed, remember that

\[\begin{aligned} \Sigma^{-1} &= \begin{pmatrix} \Omega_{xx} & \Omega_{xy} \\ \Omega_{yx} & \Omega_{yy} \end{pmatrix} \\[1em] &= \begin{pmatrix} \left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx} \right)^{-1} & -\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \\ -\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1} & \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} + \Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma{yx}\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \end{pmatrix} \enspace , \end{aligned}\]and therefore

\[\begin{aligned} \Omega_{yx} \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} &= -\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}\overbrace{\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1} \left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}\right)}^{I} \left( -\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\right) \\[1em] &= -\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx} \left(-\left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\right) \\[1em] &= \Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx} \left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \\[1em] &= \underbrace{\Sigma_{yy}^{-1} + \Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx} \left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\right)^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}}_{\Omega_{yy}} - \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \enspace . \end{aligned}\]This means that we have correctly completed the square! To clean up the business of the determinants, note that the determinant of a block matrix factors such that

\[|\Sigma| = |\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}| \times |\Sigma_{yy}| \enspace .\]Substituting this into our equation for the conditional density, as well as substituting all the $\Omega$’s with $\Sigma$’s, results in

\[\begin{aligned} f(\mathbf{x} \mid \mathbf{y}) &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma|^{-1/2} |\Sigma_{yy}|^{1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(\mathbf{x} + \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y}\right)^T\Omega_{xx}\left(\mathbf{x} + \Omega_{xx}^{-1} \Omega_{xy} \mathbf{y} \right)\right) \\[1em] &= (2\pi)^{-n/2} |\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}|^{-1/2} \text{exp} \left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(\mathbf{x} - \Sigma_{xy} \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right)^T \left(\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}\right)^{-1}\left(\mathbf{x} - \Sigma_{xy} \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}\right)\right) \enspace . \end{aligned}\]Thus, if $(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})$ are jointly normally distributed, then incorporating the information that $Y = \mathbf{y}$ leads to a conditional distribution $f(\mathbf{x} \mid \mathbf{y})$ that is Gaussian with conditional mean $\Sigma_{xy} \Sigma_{yy}^{-1} \mathbf{y}$ and conditional covariance $\Sigma_{xx} - \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_{yy}^{-1}\Sigma_{yx}$.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we have seen that the Gaussian distribution has two important properties: it is closed under (a) marginalization and (b) conditioning. For the bivariate case, an accompanying Shiny app hopefully helped to build some intuition about the difference between these two operations.

For the general $p$-dimensional case, we noted that a random variable per definition follows a (multivariate) Gaussian distribution if and only if every linear combination of its components follows a Gaussian distribution. This made it obvious that the Gaussian distribution is closed under marginalization — we simply ignore the components we want to marginalize over in the linear combination.

To show that an arbitrary dimensional Gaussian distribution is closed under conditioning, we had to rely on a mathematical trick called ‘‘completing the square’’, as well as certain properties of matrices few mortals can remember. In conclusion, I think we should celebrate the fact that frequent operations such as marginalizing and conditioning do not expel us from the wonderful land of the Gaussians.5

I would like to thank Don van den Bergh and Sophia Crüwell for helpful comments on this blogpost.

Footnotes

-

$\Sigma^{-1}$ is the main object of interest in Gaussian graphical models. This is because of another special property of the Gaussian: if the off-diagonal element $(i, j)$ in $\Sigma^{-1}$ is zero, then the variables $X_i$ and $X_j$ are conditionally independent given all the other variables — there is no edge between those two variables in the graph. ↩

-

You might enjoy training your intuitions about correlations on http://guessthecorrelation.com/. ↩

-

See also Dennis Lindley’s paper The philosophy of statistics. ↩

-

This follows from the Gaussian integral $\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-x^2} = \sqrt{\pi}$, see here. For more on why $\pi$ and $e$ feature in the Gaussian density, see this. ↩

-

The land of the Gaussians is vast: its inhabitants — all Gaussian distributions — are also closed under multiplication and convolution. This might make for a future blog post. ↩